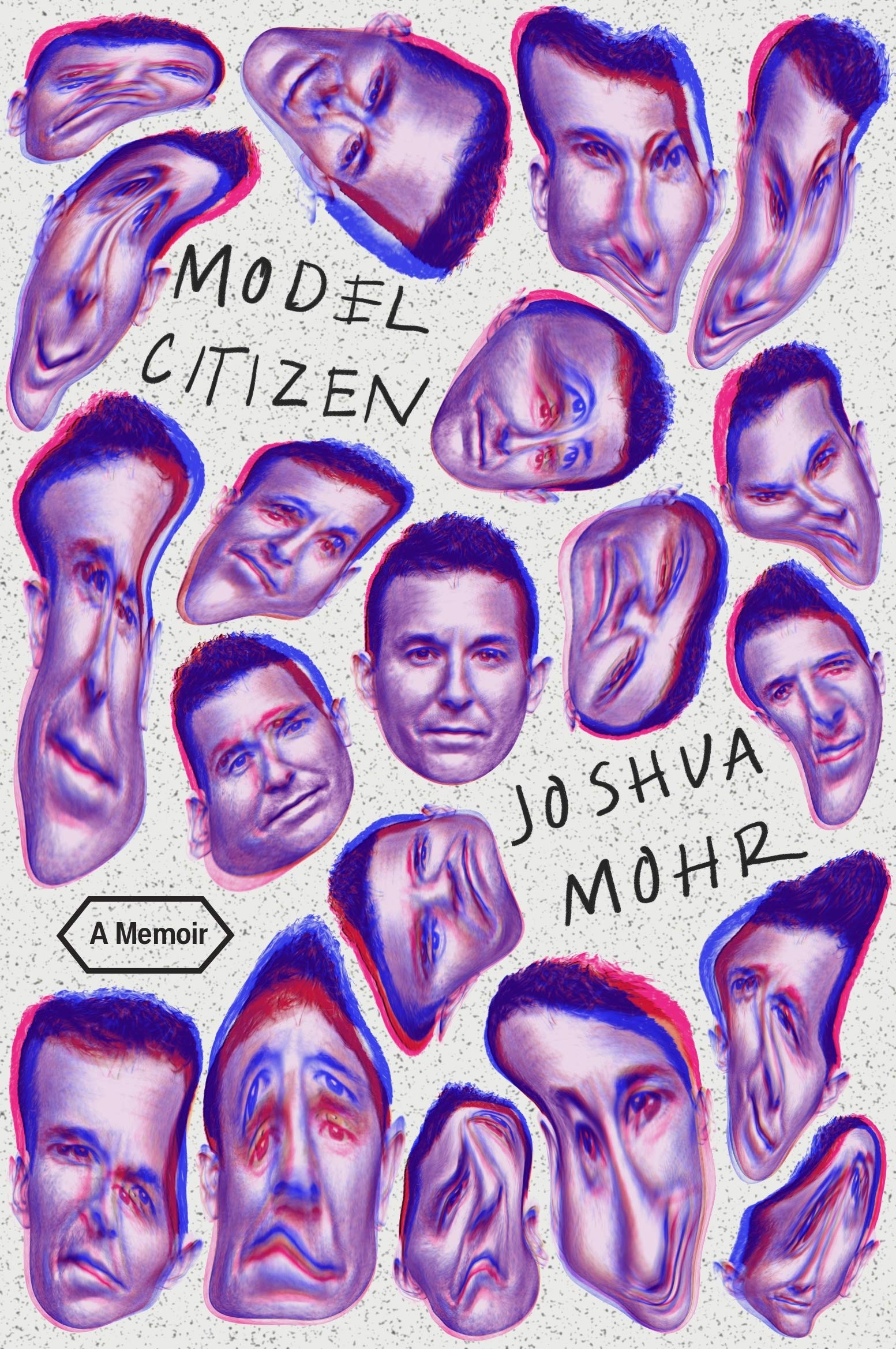

“Model Citizen” Author Joshua Mohr

May 02, 2021

All stories of substance abuse and recovery are the same, except they’re different. Josh Mohr’s memoir “Model Citizen” proves the point. An honest, raw look at one man’s journey through addiction, warts and all. Join us this time on the Behavioral Corner.

The intimate, gorgeous, garish confessions of Joshua Mohr―writer, father, alcoholic, addict

Her teeth marks in the wood are some of my favorite things. Every now and again she rips the pick out of my hand and tosses it inside the guitar . . . I hold it over my head, hole down, shaking it back and forth, the pick rattling around in there. And as it ricochets from side to side, I always think about pills. Maybe the pick has turned into oxy. Or Norco, codeine, Demerol. Maybe it’s a pill and when it falls out I can gobble it up.

After years of hard-won sobriety, while rebuilding a life with his wife and young daughter, thirty-five-year-old Joshua Mohr suffers a stroke―his third, it turns out― which uncovers a heart condition requiring surgery. Which requires fentanyl, one of his myriad drugs of choice. This forced “freelapse” should fix his heart, but what will it do to his sobriety? And what if it doesn’t work?

Told in stunning, surreal, time-hopping vignettes, Model Citizen is a raw, revealing portrait of an addict. Mohr shines a harsh spotlight into all corners of his life, throwing the wild joys, tragedies, embarrassments, and adventures of his past into bold relief.

Pulsing with humanity and humor, revealing the immediacy of an addict climbing out of the murky pit of his past, Model Citizen is a darkly beautiful, incisive confession.

Ep. 49 - Joshua Mohr Podcast Transcript

The Behavioral Corner

Hi, and welcome. I'm Steve Martorano. And this is the Behavioral Corner, you're invited to hang with us as we discuss the ways we live today, the choices we make, the things we do, and how they affect our health and well-being. So you're on the Corner, the Behavioral Corner, please hang around a while.

Steve Martorano

Hey, everybody, how are you doing? Welcome to the Behavioral Corner. My name is Steve Martorano where I get to hang for a living. It's just the greatest thing in the world. We're here and we're lucky enough all the time on the Behavioral Corner to run an interesting people. And then we sit on the stoop and we find out, you know what's so interesting about them, I guess. I got a good one for you today. As you know, we deal with the subject of behavioral health, a very broad term. Put simply, the way we behave affects our health, the decisions we make, the choices we decide on all have an impact. So you know, we had a broad mandate to talk to all kinds of interesting people. The topic of substance abuse, though, is often central to our discussions here. And I like to say in a phrase I take full credit for "All stories of substance abuse and recovery are the same, except they're different." And I gotta tell you something, no one proves that more, obviously, in my opinion than our guest. Today, Jason Mohr. Jason is a novelist of five novels under his belt by now.

Joshua Mohr

Josh.

Steve Martorano

Oh, my God, can we change your name for the purpose of the interview?

Joshua Mohr

It might be easier, right?

Steve Martorano

Now, let's just do this. I'm sorry, Jason (Josh), Jason Mohr (Josh Mohr), novelist, five under his belt, very impressive. And a couple of memoirs, as well, the latest of which Model citizen is how he came to our attention. And it's an amazing story, as I say, of substance abuse issues, and ultimate recovery from them in a matter of speaking. Jason (Josh), thanks for spending some time with us on the Corner.

Joshua Mohr

Thank you very much for hosting me today, Steve. I appreciate it. My name is still Josh, by the way.

Steve Martorano

Oh, my God. Oh, my God. Alright Josh, listen, did I get you to know what I mean when I say that all these stories are the same. except they're, they're different? Yours, when I first became aware of the memoir, and I did so through an entire review in the New York Times, the first line in the review is what caught my attention because the I don't know what you think of that review was pretty favorable. But he says you're a man without regret. And there you go, that's a new take on hey, I'm sober now. Is it true? Do you have no regrets?

Joshua Mohr

I understand why they wanted that to be sort of one of the theses that they're willing to explore in a review. I think broadly, what he meant by that is, no, I'm not trying to flog myself necessarily for the blunders and mistakes from when I was still dirty. I would argue that you know, the current iteration of you and the current iteration of me wouldn't exist without the mistakes and blunders and the lessons either learned or not learned or younger wilder days. So in that sense, like, yeah, I look back on those things and be like, God, that was probably a shitty way to do things, but it was a shitty thing to say or not say, what I look back on specific micro things that have happened and have separate ground, of course, yeah. And I'm a human with a conscience. I also think, you know, a lot of recovery people are, it's always about like, I'm so sorry, I'm so sorry. I'm so sorry. And that's not my default mechanism.

Steve Martorano

Okay. See, that's what's fascinating about this because I've done a lot of these interviews. And you often hear that and it's always heartfelt. It's always sincere about the damage done and all of that, but regression interesting thing, it's almost well unavoidable beside the point. I mean, what possible, good does rueing something to have to do with anything?

Joshua Mohr

I mean, it's an odd dichotomy for from a memoirist tool, like, obviously, you know, memory and the examination and the excavation of the past is important to me. Otherwise, I wouldn't have done the work in the first place. But that doesn't necessarily mean that like, you know, I want to just drag myself over the coals for 300 pages.

Steve Martorano

Right. There is something to that, I think, read parts of your book. I haven't gotten the whole thing yet. But what I got out of the review was the reviewer was also struck by "Oh my god, I'm so sorry this." was not the central theme of your story. So tell us a little bit about yourself and your age and where you grew up. And when the problems with I guess it started without all began for you.

Joshua Mohr

Yeah, you know, I was the products as most -- not, not every but a lot of people from my tribe, you know, like we like fire, we like chaos, because we grew up in anarchy. I was certainly the way that I came of age in Arizona, with an addict for a primary parent. So I was around, you know, booze and drugs and people making suspect and dangerous decisions my entire life. And I liked that. I was the sort of drinker I was the sort of drug person who loved oblivion. You know, like, my goal every day was to blackout from a very early age, even in junior high school, I remember very vividly being like, oh, if I drink 10 of these, if I have, you know, even more acid, like, I'll leave this place. And I liked that, from a very early age, that was something that was important to me. But you know, I don't think I would have written a memoir that was just about addiction. If this story was just, I used to do a lot of drugs. And now I don't do drugs anymore, I don't think I would have written that book. Because that books been written a kajillion times. I was interested in kind of the medical mystery of my particular story, which was, you know, in my 30s, I started to have these series of strokes. And I had three very serious ones, for they realized that I was born missing an entire wall in the middle of my heart and that the surgeons, were going to go into my heart and build a wall, which is this really cool thing that I didn't even know that they could do. So what was interesting about it, from my perspective is like, you know, yes, they can save my life. But in order for them to save my life, I had to get high on opiates for heart surgery. So really, what the surgeon was presenting me live was this really awful equation, which was, in order to save my life, I have to risk everything I've worked so hard to rebuild as a sober person. So in a sense, that becomes an existential question. It's not just a book about addicts for attics, these existential questions kind of extend the conversation to everybody in the world be like, what would I do faced in this scenario that doesn't have a right answer? How am I supposed to approach this? That question is inviting enough. And it's going to bring people into the world of the book.

Steve Martorano

Yeah, yes. And now it becomes apparent why you would move from non-fiction to nonfiction, because this is a compelling dilemma that the hero's facing, sure. So I guess you go through some kind of cost-benefit analysis, right? You're in your 30s and you had three strokes. Yeah. And you're thinking, well, am I going to die of a stroke? No matter how much intervention they do? If that's the case, or likely the case, why get clean? Did you go through all that? Oh, sure. You don't,

Joshua Mohr

It's always hard. If you have, you know, the attics brain, you know, you're you have a life sentence with a learning virus living in your mind. It's like, it's gonna try one round to make you relapse. And if that's not gonna work, it's gonna change over here or over here.

Steve Martorano

And in your case, it's it demonstrates how incredibly creative that mind is because they went, Oh, I know. Yeah. Let's give him a couple of strokes. Let's see how he handles that.

Joshua Mohr

You know, to be honest with you, Steve, the thing that really made me want to write the book is when I had the third stroke when my daughter was 18 months old, and I was convinced that I was going to die on the operating table. My surgery of that year was scheduled for March 11. So I had kind of this two-month window. When I asked my neurovascular surgeon-like, what should I be doing? And he just said, this real one chilling thing. He said, just stay alive. I was like "Fuck that's the advice?" This is even worse than I thought if that's your advice because I'm a novelist because I use the written word to make sense of things. I wanted to write this love letter to my kid, being like, you know, if I do die on the operating table, I want her to know who her father was, during his short, very flawed time on the planet. So it started as a love letter and hopefully, the entire project is imbued with that kind of visceral affection because that's really what in essence, the book is about.

Steve Martorano

Well, you know, people who are interested in this topic are going to benefit from your artistic mind. Because that's my experience talking to folks that create the way you do. They often see the real things in their life as a plot. No, this is an interesting thing. And this is going to happen and I wonder what will happen. And so we benefit from that backing up a little bit, how did you go through the standard multiple trips to rehab and go through all of that as well?

Joshua Mohr

I went to the only rehab, I only went to rehab one time. And it was, I was coming right off of a suicide attempt, you know, so it was like I was, for lack of a better word "ready," you know, when you take yourself to kind of the ultimate, awful place. That's what I really understood what the word surrender meant, for the first time in my life, which is like, I've been fighting so hard and feeling like I was the one who was going to crack the code that nobody else had been able to crack all along. And then you realize, you know, that's hubris, and that's deception. And you swallow your pride, and you finally know what capitalists surrender is and you give yourself to something greater than yourself.

Steve Martorano

That addictive mind, as we mentioned earlier, is a tricky thing. I'm reminded of that line of dialogue from the movie, the usual suspects, when they talk about the arch-criminal, Kaiser. So say, do you remember that movie course? Well, the great line is the Kevin Spacey, he's aligned is "The greatest trick that Satan ever pulled, was convincing you he doesn't exist." So you've got this addictive mind going, "No, no, you can do it, man, you can do this. Come on, get serious."

Joshua Mohr

I've been saying as I've been doing publicity for the book that I don't consider this an addiction memoir. I consider this to be a relapse memoir, which I think is a really important distinction. Although for some people that might seem as though I'm splitting hairs. The reason I think that that's important is I don't think getting clean is hard. I think most people can get clean. I think staying clean is tremendously difficult. And parts three and four, like the second half of the book, are thrusting and forcing the reader to occupy the mindset of somebody who from the outside, everything seems like it's going fine. But I'm letting them kind of be privy to those addict, you know, kind of fantastic malfunctions. That happened in our thought process. I mean, because I think, you know, people don't want to believe that the people in their lives who are clean, don't want to think about them being as vulnerable as they really are. You know, like, if you're your mom gets clean, your daughter gets clean, your sister gets clean. You want to say to yourself, they're fixed now. But I felt like my heart surgery was the perfect way to have this conversation because I had heart surgery after the three strokes. And they said to me, Josh, you're six now, and then two years later, I had another fucking stroke.

Steve Martorano

You got dealt a pretty weird hand. No doubt about it. Josh Mohr is our guest. He is a writer, a novelist, and the author of a memoir entitled Model Citizen. It's a, as I said, it is a unique look at a very common situation. people struggling with many things, substance abuse in this case, and then getting to that moment when they try to master the situation. Let me ask you about that. I don't know you use the word clarity. In your memoir, you talk about this clear moment. It's another motif that always presents itself, this moment of clarity when the substance of the user says this isn't working I've got to try something else. Let me ask you personally, what you think cuz I've wondered about this. Do you think that moment of clarity, which is difficult enough to reach is arrived at when the substance abuser has done so much damage to themselves? That they must change? Or they have done so much collateral damage to the people around them? That they must change? How was it for you?

Joshua Mohr

I think if you're if you're "lucky enough," and I'll put that word in quotation marks. If you're lucky enough to find your way to the sunny side of the street, with only collateral damage. I would call that a high bottom. I would say that's the best possible outcome and it's a horrible possible outcome. Most of us have to ruin our own lives to you know, you have to go to that place where you say like, I'm gonna die. I'm going to go to jail. I'm going to get clean. We all want to feel like we're the exception to the rule. But we're not the exception to the rule. We're the rule. And I got to this place where you know, I know, I think your most people who try to take their own lives would say that they just come to this moment where they say like, I don't know what's next. I just know that it has to take less than I ache here.

Steve Martorano

Yeah, you know, it's just something deep about human beings in general, that as you just said, it has to be personal before you want to get a handle on it. In spite of the fact of the pain, or causing to your family,

Joshua Mohr

I lost a wife. You know, I was married the first time and like, that went up in smoke. And like, you know, they always say, you know, it's 50% here and 50%, there takes two to tango. Not in the addict's world. I was well equipped to ruin that all by myself, thank you very much. I left the marriage, it was like, "Well, we just weren't compatible. It did work. Tra la la. And then like, you know, went about my merry way. There has to be that intimate, visceral thing, at least if you're programmed like I am. It had to come from like, Oh, no, I'm actually going to die.

Steve Martorano

Well, you know, self-preservation and all that. So did you run the gamut of substances? I mean, did you do it all?

Joshua Mohr

I did. I was, you know, I was, you know, we all have our favorites. You know, I mean, certainly, booze was there. I love opiates. Like, I shot Special K a lot. I also did drugs based on where I was in the day, you know, or with, like, if it's 10 o'clock at night, and I want to stay out on I like, the only logical thing to do is to get an eight ball of cocaine, of course, you know, and then I got to come down to go to sleep. So, you know, it was always like, it was all about the lifestyle, you know, in which vices in which supplies I needed to prolong the party as long as I possibly could prolong it.

Steve Martorano

Yeah, a lot of people don't understand those who either don't have a problem or don't have it in their lives. But didn't do it even recreationally the way you say you started. And everyone who's done that. And I include my generation, certainly, recreational drug pioneers, balancing the drugs in order to keep the party going.

Joshua Mohr

But I think there are people who are wired like me, where like, say you're 10 or 11 years old, and you give yourself alcohol poisoning for the first time. You know, you're getting sick, you're throwing up and you think to yourself "This is the best feeling in the world."

Steve Martorano

Yeah. The idea of a gateway drug, I think it's probably now pretty much discarded, you might think of it you anything's a good idea. You know, let me ask you about that because that's another phenomenon of substance abusers to people in recovery and it's something that a clinician told me is referred to in the therapeutic realm as euphoric recall. I don't know whether you've ever heard this expression. But it's characterized by if you've ever seen a group of people in together who are in recovery, they will begin swapping stories. Oh, you think you used to get screwed? Let me tell you about the time I went to sleep in Florida and woke up in Venezuela. Yeah. And that's called euphoric recall of the good old days. And the therapist says it's, yeah, it has to occur. But the clinician forces the person recalling to continue the story. Don't end the story with how cool it was the week that Venezuela tells about getting thrown in the prison? Sure, you must still have those moments where you go, Oh, I mean, you have a great moment in the book where you talk about, you can even step back now look at some incident in Vegas, where you're running around with your pal. When you look back at that, how do you feel about that?

Joshua Mohr

Well, in terms of their euphoric recall of it all, I mean, that happens to me a lot in dreams, like I have a lot of relapse dreams. And there, there's such a binary in that, like, I'll wake up half the time and be like, that was so much fun. Like, I was glad I got to, go back to that world for an hour without any consequences. But you know, what I was getting out of rehab -- what you were just talking about, like, keep the story going, is one of the greatest tools that I was given on my way out the door, and they went through what my counselor used to call it was just like, play it to the end. Yep. You go out to a ballgame with a friend and you see somebody else have a beer and you think to yourself, I would like a beer. Okay, well, he'll drink that beer. And then they'll go home. And you'll go to Tijuana. And you know, keep the story going.

Steve Martorano

Exactly, right. Exactly, right.

Joshua Mohr

You can kind of use those superimpositions in a way to kind of keep yourself on the straight and narrow because you can't like the seduction of that one beer is such a mirage for people from my tribe. Some people can do that. And I wish I was one of them.

Steve Martorano

Deep inside you realize that you're not part of that group. Josh Mohr is our guest just as I said, as he seems by acclamation of us. novelist and now he's written two memoirs, the latest called Model Citizen about his struggles with substance abuse, his health issues, and how he's come out the other side of that, you know, I'd like to talk a little bit about your process as a writer, and the way it works for you. When you write a novel. I don't know how you work, but I've read many writers who talk about, they don't lose control of their characters, but they sort of let the characters free. Yeah, they sit down and go, "Well, this is sort of what I think's going to happen. But who knows where it's going to go?" When you write a memoir, it's much much different, because you now know if the protagonist is going to wind up, how does it influence your writing?

Joshua Mohr

Well, I think, you know, from a novelist point of view, you're kind of discovering, during those nascent drafts, you know, maybe draft 1,2,3. You're figuring out like, the what of the story, you know, like, What the hell's the plot, what the hell is gonna happen? The what is kind of on the forefront of the novelist mind and a little bit of why as you're starting to think about, you know, the psychological and the emotional filter of the main character, and how he or she sees the world is then going to influence the plot. So it's kind of like the collision of the what and the why is what's fueling those early gusts of enthusiastic creativity. Whereas as a memoir, you don't have to worry and really ponder about what you're thinking about the how. The how meaning, like, how are you going to tell the story? Like, I know that this story that I wrote in Model Citizen has been written 5000 times and that's a generous estimate.

Steve Martorano

Last month, it was written 5000 times,

Joshua Mohr

Yes. And how do you do it in a way that people haven't heard it before? So I think you know, the, as a memoir is, the first thing that you want to do is you want the book to be a reflection about how you sound like the book needs to sound from a cadence or time signature perspective, the same way that you talk. Make it personal, you know, and I also think that the book should be a reflection of the life lift. So like, I've lived a very punk rock life. So I wrote Model Citizen to sound like a punk rock song. What I mean by that is that I left a bunch of mistakes in there. Like if it was a novel, and if it belonged to somebody that I made up, I would have sanded down additional edges. But because I wanted it to sound punk rock, I wanted the guitars to be out of tune.

Steve Martorano

And the other thing is that you know, fiction sort of has to make sense, right? Nonfiction does not have to make sense. It just has to be what it is. The other thing I was struck by in the book Model Citizen, is your ability to do just what you said, which is a really tricky thing and that is the object of the story. But write it in a way detached, right, as though you're watching it happen objectively, without sentimentality, the time saved without regret, which is a little overstated. I think, too often memoirs, memoirists, anyway, think they've got to constantly keep hitting you over the head with, "This really happened to me. And this is how I feel about it." Rather than going "Here's what happened."

Joshua Mohr

Frankly, most of that was really boring. And I think one of the reasons that I think most memoirs are really boring is it's exactly what you're talking about. It's the balancing act between the two versions of the memoirist in the book. So there's the version of the memoir is who's situated and oriented in history. And he or she is the person who's actually or, you know, going through the series of events in the book. And then there's a person who sits outside the scope of the book retrospectively, looking back, and how do you toggle fluidly and organically between those two eyes in a way that's going to make the book feel cool and serious, and sometimes memoir as lean so much on the version of themselves, outside the scope of the book, that it makes it sound like they're writing from this, like, enlightened person wisdom, which is fucking bullshit.

Steve Martorano

Yep. Yep.

Joshua Mohr

I would argue to Steve, that one of the things that unite us as a species is the fact that we're all confused. You know, we might not all be confused about the same things. But we are all confused. So I like memoir is at the beginning of the book that's like, Look, I'm a confused animal too. And I want to tell you some stuff that's been happening because I'm trying to make sense of what it means to be alive in this very bemusing world.

Steve Martorano

Well, and that's why your memoir about it. The very typical phenomenon, tragically, and that substance tribution trying to get straight again, is a particular value because it is in that vein. We're stumbling around in the dark and trying to figure out how I got here. There's a thing called an unreliable narrator. And you can enjoy that sometimes you don't know whether the person that's talking to you in the book is lying or not. In your case, in this memoir, there is the sense that the narrator, you are not so much reliable or unreliable, but just going I don't know, what do you make of this video? This

Joshua Mohr

make any sense to you? Yeah, let me know. I think there's also like a nice, there's some humility. Oh, yes. So some grace in this idea about like, trying to make write the book in such a way that it sounds like I'm sitting on the barstool right next to you whispering the story in your ear. You know, where I want it to feel that intimate that you and I are constructing this book in real-time together. I want the audience to feel as close to the action as she possibly can feel.

Steve Martorano

Yeah, yeah. Josh Mohr's is with us and that's exactly why we invited you. Because we, you know, we couldn't go into the bar, but we can hang here on the behavioral corner. Just a couple more minutes here and I want to I know you've got a hard out here coming up. You mentioned early on that your primary caregiver, as you were young, was a substance abuser, an addict, your father was absent from your life, what was it that occurred?

Joshua Mohr

Yes, my parents split up when I was young, and my mom was in Arizona. And I at that point, I think they kind of defaulted most of the early 80s, where they kind of defaulted more to like, obviously, the mother is a more reliable parent than the father is, obviously we realize, at this stage that that's not true. There was more to the story that I didn't know back then. My father was a Lutheran minister, who he's dead now. But at the time, he was having an affair with someone in his congregation. And the part of the story I didn't hear was, if you just vanish, I will help you keep this secret. Whereas if you like fight us in a custody battle, like all your dirty laundry is gonna come out. So he bolted to that time, ministers couldn't get divorced, or they would lose their job. So when they split up, he went to Berkeley, you do a Ph.D. in archaeology at Cal. And I lived with her until I turned 12. And at that point, I don't know if the laws are the same now. But back then when she turned 12, that's when the miner was allowed to say which parent they prefer to live.

Steve Martorano

Really?

Joshua Mohr

But then at 12, I said, I would like to not live with a pill-popping alcoholic anymore. So I moved to the Bay area to be to live with my father, his new life, and I had a new half-sister. And that obviously presented its own system of challenges too, right? Where you kind of get there and you're like, wait a minute. My mom was such a mass that you had to leave. But you left me behind.

Steve Martorano

Yes.

Joshua Mohr

Know you like these people more than me?

Steve Martorano

Yeah. And suddenly, you're automatically a stranger in a strange situation. Twelve years, you're able to, you know...what's wrong with that laws? If they don't give you the third option of saying, neither one of these?

Joshua Mohr

The interesting thing about my father who, you know, he died really young. He died when he was 52. And, you know, he died still really valuing his persona. And he didn't really want anybody to know him. Like he wanted the people to know this slick veneer of a charismatic, handsome minister. And because he never let me know him. It's actually one of the reasons that I wanted to overcorrect and share everything with Ava even the things that my daughter, there's no way she would want to know about me. But because I was kept from the truth. I wanted to err on the side of just blah. Here's the whole story you can sift through and make from what you want to make from

Steve Martorano

Well, you know, when you've lived and I'll use the word an "interesting life" the way you have -- problematic though it was --= what point would it be if leaving anything out? I mean, there wouldn't be any point at that if the story is worth telling -- tell the story.

Joshua Mohr

When I tour with the book, when I talk about it being a love letter, some people who have read it, I can kind of see their browse for Oh, and you know, what they're thinking to themselves is like, Josh, have you ever even read a love letter because they're not supposed to have this many felonies in them.

Steve Martorano

On the tour, are you speaking to general readers, or are you in front of AA groups are you doing both?

Joshua Mohr

You know, under the old rules of the old world, worlds, you know, when I would be doing like a physical tour, I absolutely spoke to as many, you know, NA, AA groups as I could along?

Steve Martorano

How is that crowd responding?

Joshua Mohr

Great, because they're used to people kind of talking to them as tourists, you know, and like I walk into the room and I'm like, just another disaster, you know, and we just have like a raucous good time together.

Steve Martorano

Yeah, I can see them going, "Oh, far out. He's got this book out. And he's on this tour. And he's just as confused as ever."

Joshua Mohr

Absolutely. I tried to talk to incarcerated populations as much as I can too, you know because I don't when I was in graduate school at the University of San Francisco, my first teaching job was at a halfway house. And so I had a bunch of obviously, emotional allegiances to that population, way back then. And I still try to stay as involved as I can just, you know, sharing my story. If I can help one other person that makes it all worth it.

Steve Martorano

Did you write when you are high in drinking?

Joshua Mohr

Oh, yeah, absolutely.

Steve Martorano

What is it you have any opinion on what it is with alcohol and writers? Is there a long tradition, they go hand in hand.

Joshua Mohr

I think it's the easiest way to hack into a flow state, you know, where like, it completely turns off your conscious mind and it completely empowers your sub in your unconscious. You can do the same thing with, you know, rigorous exercise and sex, meditation. There are other ways to kind of replicate that moment where, when you're really in the writing zone, there's no such thing as the past. And there's no such thing as the future. And like, that's the flow state. That's like, that's like boxing. You can't think about anything else.

Steve Martorano

Yeah, there's a suspension of time. It's the pure moment. Well, listen, the book is entitled Model Citizen. Josh Mohr our guest. Terrific, terrific job. This is one of those books about a specific topic that really can be read by anyone. If you've never had a situation like this in your life, you'll still get something from Model Citizen, if you are struggling, if you are having gotten there yet and figured it out. Again, this is pretty good...here's what happened to be by Josh Mohr. Good luck with a book.

Joshua Mohr

Thank you so much.

Steve Martorano

Are you working on something you'd back working on something else gets something else in the pipeline? Oh,

Joshua Mohr

I'm always scribbling so my next book is going to be called Get Rich. About the first female poker dealer in gold rush San Francisco.

Steve Martorano

Oh, really?

Joshua Mohr

It's my first historical novel. It was a blast to put together I can't wait to share it with people.

The Behavioral Corner

Terrific. Josh Mohr. Thanks for joining us on The Behavioral Corner. Really appreciate it.

Joshua Mohr

Keep fighting the good fight. Steve. Thanks.

Retreat Behavioral Health

Every storm runs out of rain according to the great Maya Angelou. Her words can remind us of one very simple truth -- that storms do cross our paths, but they don't last forever. So the question remains, how do we ride out this storm of COVID-19 and all the other storms life may throw our way? Where do we turn when issues such as mental health or substance abuse begin to deeply affect our lives? Look to Retreat Behavioral Health. With a team of industry-leading experts. They work tirelessly to provide compassionate, holistic, and affordable treatment. Call to learn more today. 855-802-6600. Retreat Behavioral Health -- where healing happens.

The Behavioral Corner

That's it for now and make us a habit of hanging out at the Behavioral Corner. And when we're not hanging, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, on the Behavioral Corner.

Subscribe. Listen. Share. Follow.

Recent Episodes